Today, we are starting a new series.

It's inspired, in part, by a conversation I recently had with Stephen Mansfield for a forthcoming episode of The Exchange. Stephen has a new book on the importance of understanding the faith of presidential candidates. He is the author of The Faith of George Bush and The Faith of Barack Obama, two very well-known books on these very issues.

So, we've reached out to the 2016 presidential candidates—all of them from the major parties—and asked them to do brief interviews about their faith and how it impacts their approach to governance.

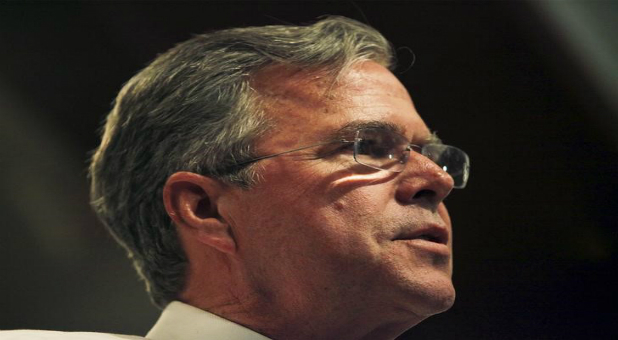

Recently, I interviewed Gov. Jeb Bush about his faith.

Gov. Bush is a convert to Catholicism and a practicing Catholic. He speaks regularly and freely of his faith and conversion experience. In this brief interview, I ask him about his faith and its implications for his approach to governance.

On Catholicism

ES: We know you converted to Catholicism—I want to talk about what you mean by that phrase. At one point you said, "Christ came into my life a little bit earlier but I converted to being Catholic." So tell me about what happened before you were Catholic or how Christ came into your life "earlier."

JB: In the late 1980s, it just was a time when I was being and doing and going—just going a hundred miles an hour in trying to run my business, be involved in civic and political stuff and trying to be a good dad and a good husband. It just became overwhelming, and I forced myself to get quiet and started reading the Bible quietly and it just gave me—it wasn't like what people would call a "born-again experience"—like a moment where there was a flash or anything like that—it's just the serenity that I had reading the Gospels just converted me to a Christian.

ES: So before that you just were, generally, what? What would you describe yourself before that quiet moment?

JB: Well I was a church-going—we attended Mass because my wife was Catholic, and I wanted my children to grow up in the Catholic faith—the faith of their mom.

I was observant I guess, I don't know, but it wasn't a deep relationship... It was an important part of my life but it wasn't an integral part of my life.

ES: So first, then, it becomes a more integral part of your life, reading of the Gospels you have some sort of encounter, and it becomes central to your life. And then you subsequently attended RCIA [Rite of Christian Initiation] class. Tell me about that.

JB: It was wonderful. It was an amazing experience. It was after the election, so I kind of had to play catch up. It started in September, and I joined maybe the second week in November, literally right after the election.

I didn't have a sponsor. I kind of got adopted by all of the sponsors. These were lay leaders in the church, just wonderful people.

There were six or seven people participating for different reasons. One wanted to get married. It was just normal people for all sorts of reasons wanting to become Catholic.

I looked forward to it in the evening, a couple of hours every week that we had a chance to get together.

ES: In the past, Catholic candidates have tended—particularly if we go back to J.F.K. and others—to downplay the impact of their Catholicism on their views, on their politics and how they would govern. When I read your comments, it seems to me that you've been clear that this impacts the way that you are going to lead and to govern. In what ways would it impact?

JB: I don't think you can separate your faith and kind of put it in a lock box and not be informed by it. It's an integral part of who I am, so why wouldn't it be a significant part of how I would govern? I've never understood that [why it wouldn't be central to governing] and say it definitely—that as governor I [had the] belief and, best I could, acted on the belief that life is a gift from God. And I embraced it.

We changed the programs and funded the programs that had been languishing for the development of the disabled.

Adoption programs were horrific. The child welfare system was way under water. We were the first state to embrace a community-based model for child welfare. A number of the disabled programs were going to be taken over by a federal court and we transformed them and 31,000 families got off a waiting list. ...

Certainly on the questions of life, I got to act on my beliefs in a way that I hope drew people towards the cause that life is sacred—that it's a true gift from God and that we should protect it from beginning to end.

On Life and the Death Penalty

ES: I think people know you for some of those issues. ... But probably one place with the most evident the difference between you and your church would be in the death penalty. How do you kind of navigate that as a Catholic?

JB: That's a good question. I struggle with it.

I've tried to explain it, but sometimes in life it's not an either/or—it's not so simple. We're always confronted with challenges where one's values come into conflict and this was a perfect case of that.

I was very uncomfortable signing death warrants, but I think it was because it was the law, No. 1.

No. 2, I think because I met families that, in their minds, justice was being denied by the delays. They could not get closure in their lives until the death penalty was complete and was executed. You know, these are egregious crimes.

Very few people make it to death row. They languish there because of our twisted court system ...

I felt committed to doing it because of the hurting families because of these horrific crimes, and we had a duty to do this.

It was a point of contention between myself and the bishops who would come every year to the Red Mass ... [They] always ended the breakfast respectfully but unfortunately saying, "Did you change your mind on the death penalty?"

ES: And did you say yes, no? Or where would you be on it now?

JB: I said with all due respect I'm going to maintain—I'm going to continue to respect the laws of the state ... I think if you asked the bishops or the people who worked at the Catholic conference they would say I was a very supportive governor, but for this point.

ES: If you had a clean slate would you wish that the death penalty wasn't the law of the state or do you support the idea that the death penalty is the law of the state?

JB: I support it, but here's what we tried to do and the courts basically ignored it. We tried to make the death penalty a deterrent by having it be complete within five years instead of 25 years.

I don't think it's a deterrent effect—it doesn't have a deterrent effect when there's no certainty at all whether it will be complete. We tried by special session to change that.

I also modified [the law] at least—there was nothing in the law that would require me to do this, but I did not sign death warrants for people who were close or below what now is the norm related to IQ.

So this was a big deal for me. It was not an easy thing to do. I took my time to really go through it. I did not relish my participation in this, but I do think that we were denying justice for a whole lot of people who were suffering.

On Pope Francis

ES: So you wrote a little bit about your admiration for Pope John Paul II. I wonder, how do you see Pope Francis?

JB: Well, I admire him because he's got this unique ability to get people to think differently about all sorts of important things: about mercy, about forgiveness, about love. Now you know the obligation that we have to be stewards of the environment. All those things I admire, and he has a style about him that's so refreshing.

So I'm a fan on that level. I do think that—I passionately believe that free market economics—a liberty-oriented economic policy creating high sustained growth needs to be recognized as the best means for people to be lifted out of poverty.

I'm not sure that the teachings of the Pope—I don't think he embraces that idea to the extent that I would love for him to do it. But he's not here to be teaching economics. It's not his job. ...

It's interesting that Pope Francis' people pick and choose what they like to hear and they ignore—you know he'll say something that is kind of paradigm-shifting in terms of getting people to think differently, but people don't read the full context of what he says about family and about life issues, about a lot of things. People kind of do pick and choose what they want to hear.

That's why he's pretty remarkable and quite popular in the here-and-now sense. I think [in] every major institution—it's always important to have a change and to have a fresh approach, and John Paul did that and certainly Francis has done it as well.

On Multireligous America

ES: How would a practicing Catholic president govern in a nation of many people of different faiths and no faiths?

JB: Good question. I think using the [bully] "pulpit," using the public forum to talk about the tenets of the faith in a way that draws people together. We're at a point in time in our country that has great divides and I think people in public life need to figure out ways to rebuild the consensus about how our society is to function going forward.

My view is I can inform people about my faith in a way that doesn't turn people off. I can get better at that—and that's what we need to do. The Catholic faith or Christianity in general is a loving faith. I find it amazing that on the public square these days you're under the impression somehow Christians are hateful people, [and that's] just not the case.

So protecting religious freedom. Explaining why it's important that the First Freedom be protected because there are other freedoms that are at stake as well. Talking about these moral issues in a way that doesn't divide but tries to bring common focus. I think that's what you do as president. And when policies make it clear you're not—you be who you are.

You're not going to put your faith in a lock box. You know, fight for the things that you truly believe to be true.

Note: Feel free to discuss the governor's thoughts and answers, but follow the comment rules, etc. Ed Stetzer will be interviewing Senator Marco Rubio next and more have committed.

Ed Stetzer is the executive director of LifeWay Research. For the original article, visit edstetzer.com.

Get Spirit-filled content delivered right to your inbox! Click here to subscribe to our newsletter.

Dr. Mark Rutland's

National Institute of Christian Leadership (NICL)

The NICL is one of the top leadership training programs in the U.S. taught by Dr. Mark Rutland. If you're the type of leader that likes to have total control over every aspect of your ministry and your future success, the NICL is right for you!

FREE NICL MINI-COURSE - Enroll for 3-hours of training from Dr. Rutland's full leadership course. Experience the NICL and decide if this training is right for you and your team.

Do you feel stuck? Do you feel like you’re not growing? Do you need help from an expert in leadership? There is no other leadership training like the NICL. Gain the leadership skills and confidence you need to lead your church, business or ministry. Get ready to accomplish all of your God-given dreams. CLICK HERE for NICL training dates and details.The NICL Online is an option for any leader with time or schedule constraints. It's also for leaders who want to expedite their training to receive advanced standing for Master Level credit hours. Work through Dr. Rutland's full training from the comfort of your home or ministry at your pace. Learn more about NICL Online. Learn more about NICL Online.